Idempotency in System Design: Full example

Idempotency is a concept frequently mentioned in system design. I will explain what it means in simple terms, briefly address common misunderstandings, and finish with a full example.

What Is It?

Something is idempotent if doing it once or multiple times gives the same outcome.

In other words, if I do that something once, I get the same result as when I do it 2 times or 3 times or 10 times. Let’s look at the standard example: we have an on and off button. Pressing them is an idempotent operation. If you press on once, the machine is on. If you then press it again, and again and again, nothing changes. The machine stays on. Same for the off button.

Here’s an example from programming:

def hide_my_button(self):

self.show_my_button = False

This is clearly idempotent.

def toggle_my_button_visibility(self):

self.show_my_button = not self.show_my_button

This is of course not idempotent.

It’s not about the return value!

This is a common misunderstanding. One could implement the hide function from above like this as well:

def hide_my_button(self):

has_something_changed = self.show_my_button

self.show_my_button = False

return has_something_changed

So we return whether something was changed or not. If we call this multiple times, the returned value might differ! But it’s still idempotent because idempotency is about the effect produced on the “state” or “effect” and not about the response status code received by the client.

Idempotent vs Pure

Although pure is not a topic of this article, I still want to address this quickly because it’s a common source of confusion.

A function or operation is pure if, given the same input, it always produces the same output.

def square(my_number):

return my_number ** 2

This is a pure function. square(3) will always be the same number.

def square_with_randomness(my_number):

return (my_number ** 2) * random.uniform(0, 1)

This is not a pure function. square(3) will almost always be a different outcome since we multiply it with a random number between 0 and 1. Likewise, if we would multiply it with some global variable or some class variable, it would no longer be pure. The global variable can change and then our outcome would be different.

Okay, let’s look at def square(my_number) again. It’s pure. But is it idempotent? Of course not. Apply it once to 2 and we get 4. Apply it again and we get 16. So a different number!

It’s also easy to find an example of an idempotent operation that is not pure. So the two concepts are totally different things!

Idempotence in System Design

So why is it such an important concept in system design? There are many reasons and we will discuss the most common ones.

Message Processing

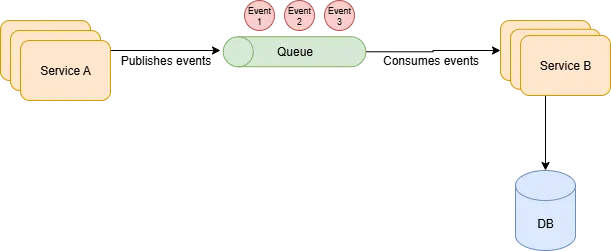

Suppose we use event-driven design in our system. Concretely, we have a message queue and a service consuming its messages.

The problem is this. When Service B consumes a message, let’s say the message containing Event 3, it processes it, and then writes to our DB. Let’s keep it super simple, suppose Service B calculates some complex formula for each event and writes the result to our DB. Now it’s very important that nothing here gets lost ever. We have very important data!

But if Service B crashes during the calculation, or there is a network partition between Service B and the DB, or something else happens, then the message and the event are lost forever. Terrible.

The solution is simple: instead of removing the message immediately from the queue, we wait for Service B to be finished, which includes writing to the DB, and then remove the message.

But this introduces a new problem. It’s possible that the same message is read twice. For example, Service B performs the calculation and writes to the DB, but then something happens. It crashes for example. So before the message is removed from the queue, the service has crashed. What happens? The service restarts, and once it’s up again and running, it will continue consuming messages. And it starts with exactly that last message. So that message gets consumed twice!

How do we solve this? We can’t really directly. System design is always about trade-offs: Either we might lose messages or we might consume the message more than once.

But that’s not so problematic! If we design the operation of Service B to be idempotent, then nothing happens. The service will consume the message a second time, but it doesn’t matter because the operation is idempotent. So the outcome is still the same.

The only downside is a little bit of extra complexity (you need to come up with a way to make the operation idempotent) and a little bit of compute resources (potentially doing the same thing more than once unnecessarily). But usually, and definitely in our case, it’s better than losing messages!

At-Least-Once + Idempotency = Exactly-Once

Here’s the key insight: message queues like AWS SQS offer at-least-once delivery semantics. That means your message might arrive once, twice, or more. But if you combine that with an idempotent operation, you effectively get exactly-once semantics. The message might be processed multiple times, but because the operation is idempotent, the business outcome is the same as if it were processed exactly once. This is a practical and elegant solution to a hard distributed systems problem.

Pitfalls

There are several things to be careful with here. One thing that can happen is an infinite loop (a catastrophic failover). If you have an “ill” message, for example of an invalid format, that makes your consuming service crash (Service B), it will stay on the queue. Meaning, Service B restarts just to consume the same ill message and crash again. And over and over. Even if your system doesn’t have such issues, they will sooner or later arise, so you really should make use of a so called dead-letter queue (or message hospital).

Other Uses of Idempotency

We’ve talked about message processing, but idempotency shows up everywhere in system design. Let me walk you through the other most common ones.

APIs

If you’re building REST APIs, you’re already dealing with idempotency whether you realize it or not. The HTTP protocol actually defines which methods should be idempotent:

GET requests don’t change anything on the server, so they’re naturally idempotent. Call them 100 times, same result every time. You can refresh a webpage as many times as you want without worrying.

PUT requests should completely replace a resource. If you PUT the same data twice, you get the same outcome. Think of it like overwriting a file - doing it twice doesn’t change anything.

DELETE requests should delete a resource. Delete something that’s already gone? It’s still gone. No problem.

POST requests are usually not idempotent by design. Each POST typically creates something. But you can make them idempotent with idempotency keys. Here’s how it works: you send a unique ID with your request (often in a header), and the server remembers “I already processed this ID, so I’ll just return the same result instead of doing the work again”.

def create_user(request):

idempotency_key = request.headers.get('Idempotency-Key')

# Did we already process this exact request?

if idempotency_key and already_processed(idempotency_key):

return get_cached_response(idempotency_key)

# Nope, create the user

user = User.create(request.data)

# Cache the response for next time

if idempotency_key:

cache_response(idempotency_key, user)

return user

Databases

Database operations love being idempotent too. Here are the most common patterns:

UPSERT operations (INSERT or UPDATE if exists) are naturally idempotent. Run an upsert 10 times with the same data, and you get the same result every time. The record either gets created once or updated to the same values multiple times.

Distributed Systems

In distributed systems, things fail constantly. Networks partition, services crash, hard drives die, and yes, occasionally cats do walk over keyboards. So we retry operations all the time. But retries only work safely if your operations are idempotent.

Full Example: Order Processing System

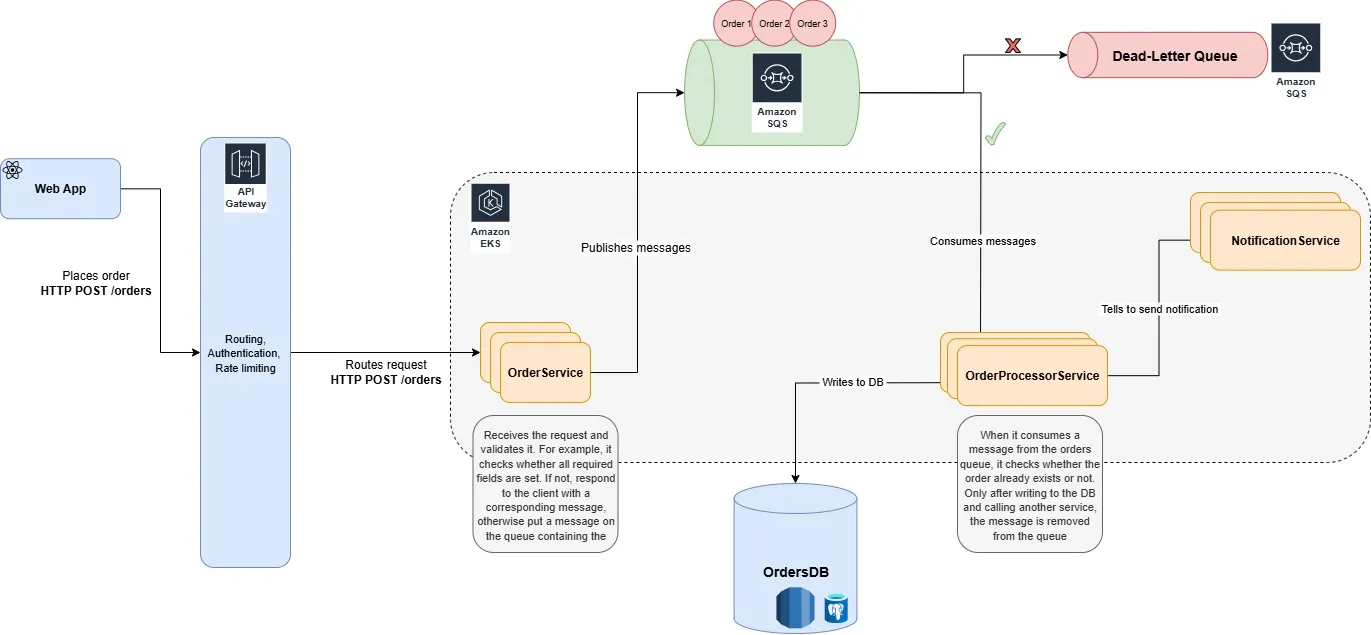

Alright, let’s put this all together with a concrete example that matches the system in your diagram. We have a simple order processing pipeline: orders come from a web app, get validated by an order service, go into a queue, and then get processed by an order processor service that writes to a database.

What We’re Building

The system is straightforward:

- Web App sends HTTP POST requests with order data

- API Gateway handles routing, authentication, and rate limiting

- Order Service validates the order and publishes it to the queue

- Amazon SQS holds the order messages

- Order Processor Service consumes messages and writes to the database

- Orders DB stores all our order data

- Dead-Letter Queue catches any poison messages

- Notification Service sends confirmations to customers

The key here is that the Order Processor Service needs to be idempotent.

Making the Order Processor Service Idempotent

The Order Processor Service consumes messages from SQS and does the actual business logic.

When we process a message, so an order event, we want to:

- Check if it was processed already

- If not, insert it into our OrdersDB

- If not, tell NotificationService to send a notification

This is idempotent because we check if it was processed already. That could be for example by doing a SELECT in the OrderDB and only inserting if it’s not there yet. Something similar can be done for the NotificationService, or inside the NotificationService with its own DB.

However, note that we need to deal with concurrency issues. What if we have two different instances of OrderProcessService processing the same message? And they both execute the SELECT at the same time. We would process the message twice, not good. So we need to wrap this logic into a transaction.

We would end up something like this:

Another note: We should to make the system actually fully resilient, put a queue in between OrderProcessService and NotificationService as well and do a similar thing.

Idempotency Has Scope

Here’s another common misunderstanding: people sometimes think idempotency means that nothing changes at all when you call an operation multiple times. That subsequent calls have literally zero impact on the system.

That’s not quite right. Idempotency applies to the business operation, not to the entire system state.

For example, suppose we have an idempotent payment processing operation. If you call it three times with the same payment details, you should only create one transaction in the database. That’s the business operation - it’s idempotent. But that doesn’t mean nothing happened on the second and third calls:

- We still logged the call in our logs

- We still recorded the response time and collected monitoring metrics

- We still validated the request

- We still checked if we’d processed it before

All of that can (and should) happen. The key point is this: the underlying business operation that we are considering idempotent, not the entire state of the system. You should absolutely log the fact that a call was received. You should absolutely track metrics about it. Those are side effects that don’t contradict idempotency.